Introduction to Probability Distributions

In Chapter 4, we introduced the idea of random processes, i.e. situations

in which the outcome can not be determined perfectly in advance. Random processes

are defined in terms of the collection of possible events (sample space) and their

associated probabilities. In that chapter, we saw three methods for calculating

probabilities – the enumeration method, the probability function method, and the

simulation method. In this chapter we will expand on the probability function

method, which uses a known function called a probability distribution to

determine the probability of each event.

Probability distributions are closely related to random variables, numeric

variables that can take on different values depending on the outcome of a random

process. In previous mathematics courses you may have seen variables such as

\(x\) or \(y\) used as placeholder values which are then solved for. For example,

you can solve for the variable \(x\) in \(4x + 5 = 25\), to determine \(x = 5\). By

contrast, the outcome of a random variable is not be predetermined. Instead,

we talk probabilistically about the likelihood of observing each possible outcome.

Random variables are typically denoted with capital letters, e.g., \(X\) or \(Y\),

whereas the observed outcome of the random process is denoted with lowercase letters

\(x\) or \(y\). For example, flipping a coin three times is a random process. We can

define the random variable \(X\) to represent the number of heads we observe

between the three flips. \(X\) can take on four possible values: 0, 1, 2, or 3. If

we observe 2 heads, we have \(x = 2\).

Most simply, a probability distribution (often just called a distribution)

is a method for taking a possible event as input and giving us the corresponding

probability as output; the corresponding probability tells us how likely it is

that the specific event will occur, out of all of the possible events. We often

say random variables have or follow a probability distribution, as the

distribution quantifies the probability of observing the possible values a random

variable can take on. We can denote a probability distribution as \(P(X = x)\), or

the probability that the random variable, \(X\), takes on a generic value, \(x\).

There are many useful probability distributions that have

been defined by mathematicians and statisticians to describe a variety of scenarios:

Counting the number of successes in a fixed number of trials that can results

in either success or failure, such as counting the number of heads when flipping a

coin three times

Counting the number of successes before the first failure in a series of

success/failure trials, such as counting the number of days before a light bulb

burns out

Describing the length of time between events that occur at a constant rate, such

as the time between phone calls at a help desk

Describing range of continues values, such as the blood pressure in adults

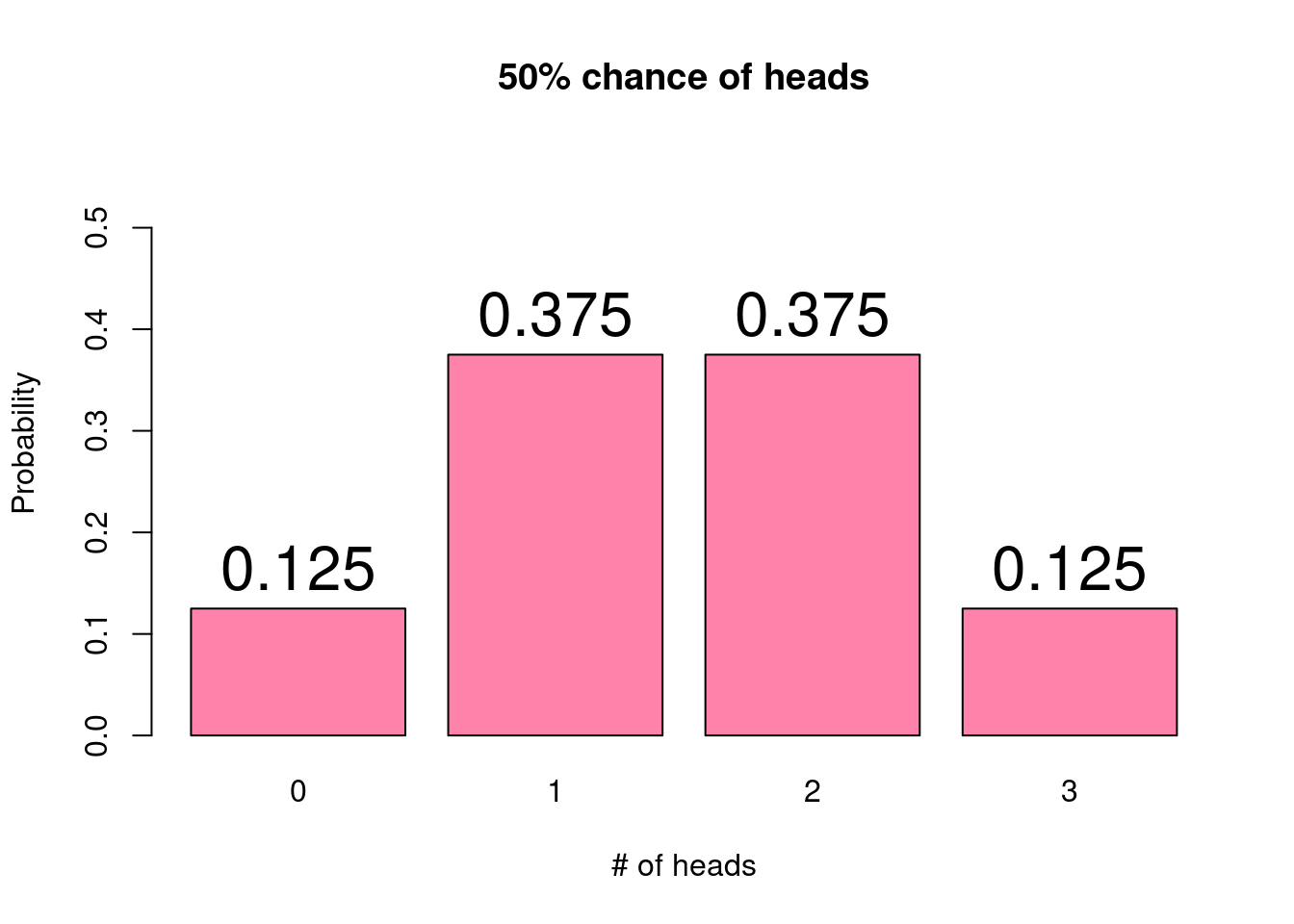

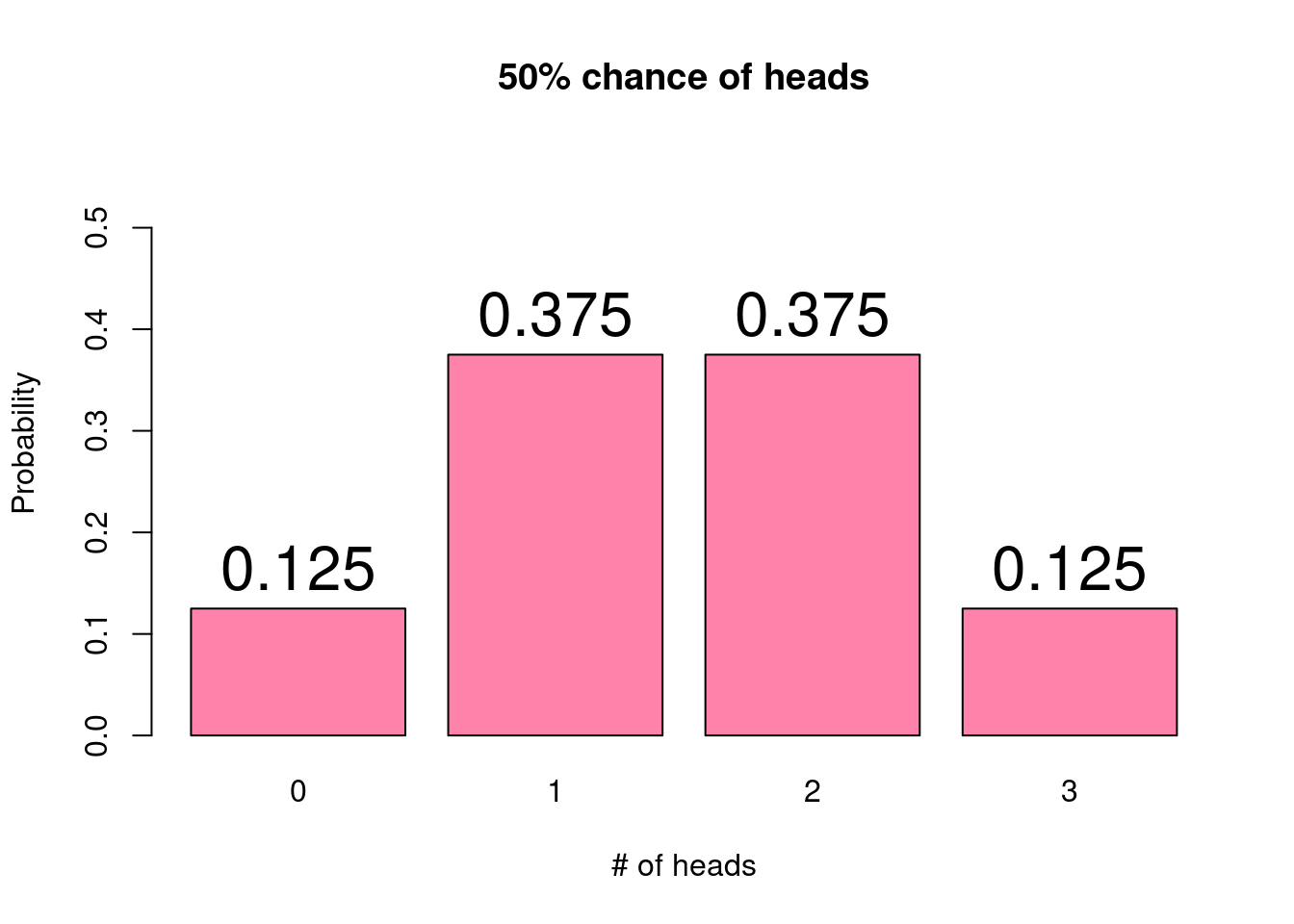

One can represent a probability distribution visually using a probability histogram.

On the x-axis, we have the possible outcomes of the random process – the values

the random variable could take. For each outcome, the bar height represents

the probability of observing that value. For the coin flipping example, the

probabilities of observing each possible number of heads can be represented as:

When looking at a probability histogram, we can characterize the shape of the

distribution analogously to how we talk about a histogram of observed data. We

often use unimodal distributions, which may or may not be skewed. For example,

the above probability histogram shows a unimodal and symmetric distribution.

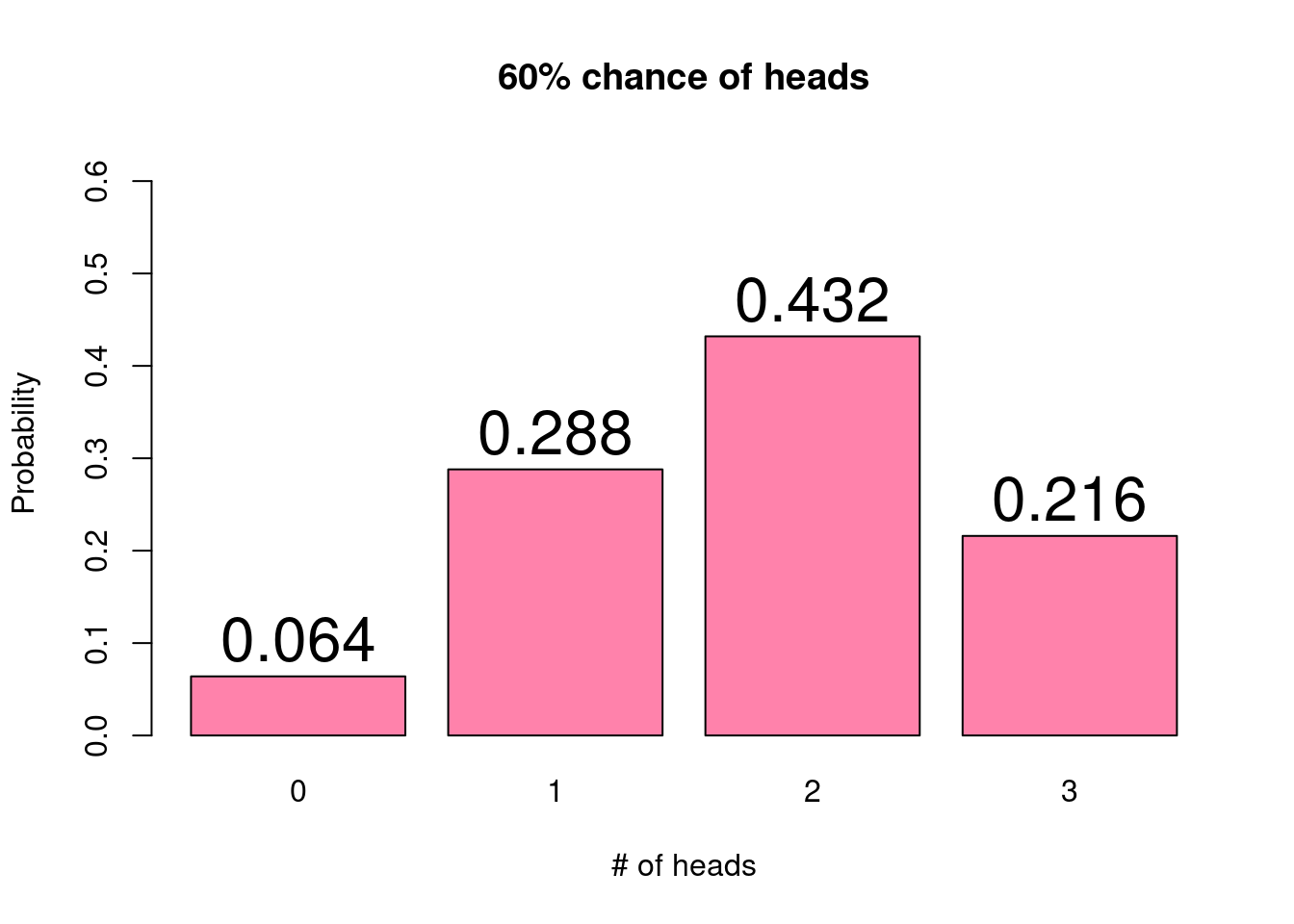

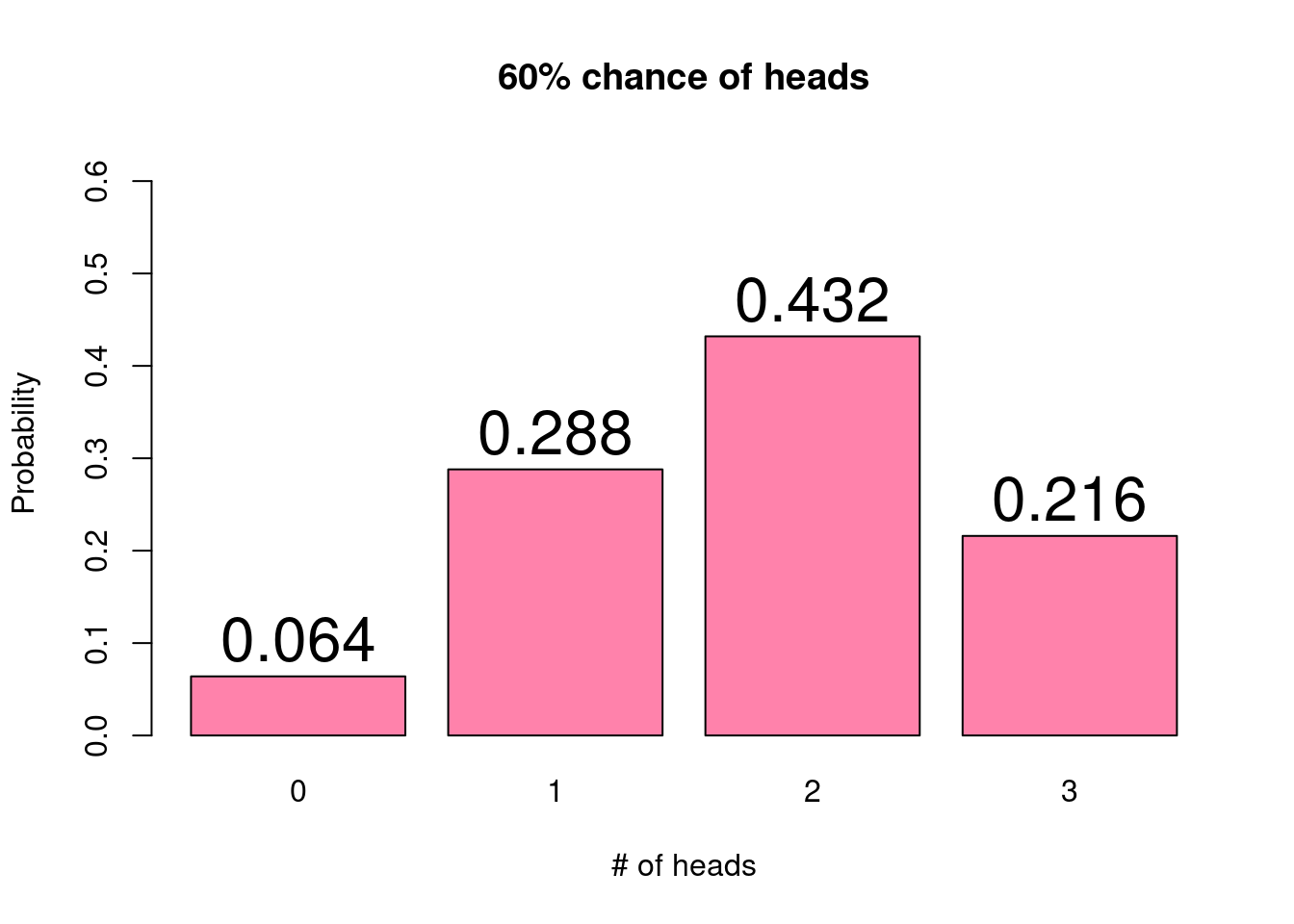

The beauty of using probability distributions to describe the likelihood of all

outcomes of a random process is its simplicity. Probability distributions rely

on a small number of parameters which determine the distribution’s shape. In

the coin flipping example, we could consider one of the parameters to be the

probability of obtaining heads. We assume that we have a fair coin and that this

probability is 50%. If instead we had a weighted coin with a 60% chance of

landing on heads, the probability distribution would change. That is, the probability

associated with each possible outcome would be different.

With a higher chance of the coin resulting in heads, we now see that the three

flips are more likely to result in 2 or 3 heads and much less likely to result

in 0 heads. In other words, the distribution is now slightly skewed left.

Because these probabilities can be described by a distribution function, we can

easily compute and compare the probabilities of each possible outcome as a function

of the distribution parameter, in this case, the probability of flipping heads.

Another key concept related to probability distributions and random variables is

the idea of the expected value, often denoted \(E(X)\). The expected value of a random variable, often

denoted as \(E(X)\), is a weighted average which provides a measure of the central

mass of the probability distribution. The expected value averages over all possible

outcomes of the random variable with each outcome weighted according to its

probability. We can also think of the expected value of a random variable as its average

value. In more technical terms, we might say that the expected value is a weighted

average which provides a measure of the central mass of the probability distribution,

averaging over all possible outcomes of the random variable with each outcome weighted

according to its probability. Whew!

Returning to the coin flipping example with a fair coin, we have

seen that the probability distribution is:

|

x

|

P(X = x)

|

|

0

|

0.125

|

|

1

|

0.375

|

|

2

|

0.375

|

|

3

|

0.125

|

Multiplying each possible outcome (\(x\)) by its associated probability (\(P(X=x)\))

and adding them together (which happens to be the definition of a weighted average)

gives us an expected value of

\[(0 \times 0.125) + (1 \times 0.375) + (2 \times 0.375) + (3 \times 0.125) = 1.5.\]

Looking at the probability histogram, this value should make sense as it falls

right in the center of the distribution.

Expected values are more easily conceptualized in terms of a game or bet. For

example, consider the following game: you flip a fair coin; if the coin lands on

heads, you win $20, and if the coin lands on tails, you lose $1. Would you play

this game? Assuming you have a spare dollar, the answer is probably yes. Since

you have equal chances of the coin landing on heads or tails, you are just as

likely to win $20 as you are to lose $1. In terms of the expected value, it

would be

\[(20 \times 0.5) + (-1 \times 0.5) = 9.5.\]

The expected value tells us that if you were to play this game over and over,

you would be expected to win $9.5 per game. Critically, it is worth reiterating

here that for any single instance of this game, you can only win $20 or

lose $1. The $9.50 indicates the long term average over many games.

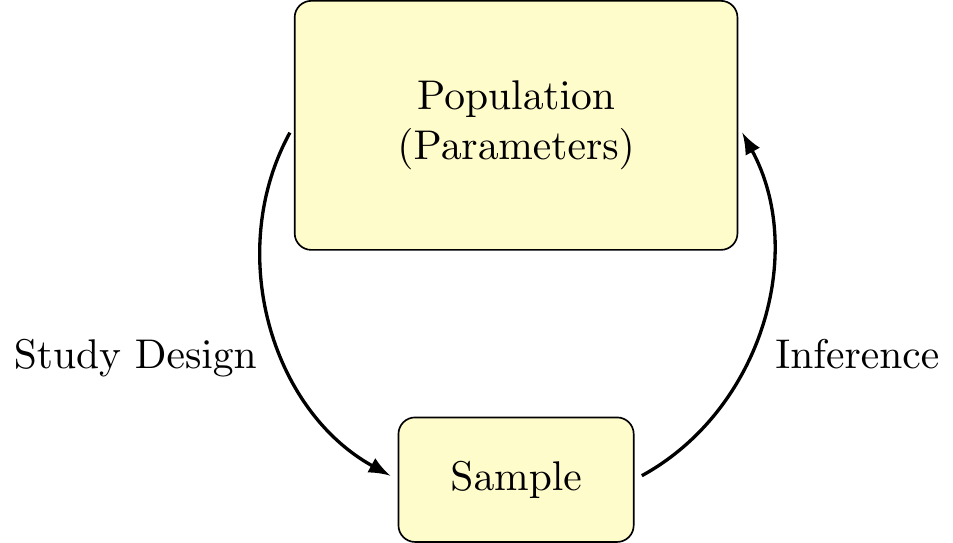

Finally, let’s discuss how probability distributions relate back to our general

statistical framework. In our framework, we are interested in learning about the

population, which we assume follows some probability distribution. This distribution

is governed by a set of unknown parameters. When we collect a sample, we expect

that the distribution of the sample will be similar to that of the true population.

As we will see in the following chapters, our sample will be used to compute statistics,

or estimates of the true parameters. Indeed, much of statistical inference involves

estimating the values of these parameters, with associated measures of certainty.

We end this chapter with a discussion of two of the most commonly used distributions,

the binomial and the normal.

Probability distribution: A method for assigning probabilities to all possible events

Random variable: A numeric variable whose value depends on the outcome of a random process

Probability histogram: A graphical display of a probability distribution

Parameters: Values associated with a probability distribution that determine the distributions shape

Expected value: The weighted average of the outcomes of a random variable, with weights determined by their probability

Statistics: Values computed from a sample that serve as estimates of the

population parameters

Binomial Distribution

The first distribution we will examine in depth is the binomial distribution,

describing the number of successes in a fixed number of independent trials

that can result in one of two outcomes (success or failure), where the probability

of success is the same between trials. As the data from a binomial distribution

fall into distinct categories, the binomial distribution is also a member of a category

of distributions known as discrete distributions.

We have already seen one example of the binomial distribution in detail – flipping

a coin some number of times and counting the number of flips result in heads (success).

Each flip has two possible outcomes (heads or tails), the same probability of heads

on each flip (50%), and a predetermined the number of trials (three flips).

To illustrate another example of the binomial distribution, we might consider

rolling a six-sided die a number of times, counting the number of rolls that result

in either a 5 or 6. That is, we would consider a success to be rolling a 5 or 6, and

a failure to be rolling a 1, 2, 3, or 4. As there are six equally likely outcomes,

with two of these being considered a success, we note that for any particular roll

(trial), the probability of success is 2/6, or 1/3. The takeaway here is that, even

though there are six possible values for a given roll, we can still posit a binary

outcome and determine the associated probabilities.

As you may have noticed from these two examples, the binomial distribution

can be used for various success probabilities and numbers of trials. In fact,

these quantities define the two parameters of the binomial distribution. These

parameters are typically denoted as \(n\), the number of trials, and \(p\), the probability of

success. The binomial distribution can be written as a function of these parameters:

\[

P(X = x) = \binom{n}{x} p^x (1-p)^{n-x}.

\]

While this may look like a nasty formula, don’t be afraid! Probabilities following

a binomial distribution can be easily computed by any statistical software. For

this reason, we will focus on the distribution properties rather than performing

calculations.

For any valid value of \(n\) and \(p\), we can use the binomial distribution

to compute the probability of observing any possible outcome. Valid values of \(n\)

and \(p\) simply mean that the number of trials conducted must be a positive integer

(e.g., 1, 2, 3, …) and that \(p\) must be between 0 and 1 (it is a probability after all).

The expected value of the binomial distribution is given by \(E(X) = n \times p\), or

the total number of trials times the probability of success for each trial. To gain

a better understanding of how these parameters impact the shape of the distribution,

we will use the following applet.

The applet below is designed to help you get familiar with the parameters of the

binomial distribution, and how they impact the probability distribution.

You can change the values of the number of trials \(n\), and

the probability of success \(p\), and the app will display the associated distribution

in a probability histogram.

Use the applet to answer the following questions:

Set \(n = 10\), and change the value of \(p\) (note: you can press the triangular

“play” button to have the app vary \(p\) automatically). What happens to the shape of the

distribution as \(p\) gets closer to 0? What about when \(p\) gets closer to 1?

Now, set \(p = 0.4\) and vary \(n\) over the range of possible inputs. What do

you notice about the x-axis as \(n\) is changing? Explain this trend by referring

back to what \(n\) represents.

Keeping \(p\) constant and varying \(n\) between 20 - 50, does the shape of the

distribution change? What about the location of the distribution?

The applet below is designed to familiarize you with data generated from the

binomial distribution. That is, we are interested in exploring the relationship between an underlying theoretical distribution and data that is observed. You can change the values of the number of trials \(n\), and

the probability of success \(p\) to specify the parameters of the population

distribution. Then, you can take a random sample from the distribution.

Use the applet to answer the following questions:

Set \(n = 10\) and \(p = 0.5\). Starting with a sample size of 10, simulate data a number of times and observe the histogram of the observed data. What do you notice? Is the observed data typically centered around the same value as the probability distribution? Does it have the same shape? Try again with a sample size of 50. What has changed? What stays the same? Do this once more with a sample size of 100.

What are some general observations that can be made from the results in saw in (1)? How consistently does a histogram of the observed data match that from the theoretical distribution? What effect does sample size have on this consistency?

Play around with different values of \(n\) and \(p\), as well as with different sample sizes. What are some trends that you notice? Are there values of \(n\) and \(p\) that seem to produce more consistent results? If you were to only look at the observed data, how confident do you feel that you could guess the shape of the underlying distribution? How close might you be?

In general, how would you describe the histogram of the binomial distribution? Does it tend to be symmetric? How do different values of \(p\) change the skew of the distribution? How about different values of \(n\)?

Binomial Distribution: A probability distribution that characterizes the

probabilities of observing some number of successes in a fixed number of

trials, each with two possible outcomes and the same probability of success

Discrete Distribution: Any probability distribution that depicts the

occurrence of distinct, countable values

Normal Distribution

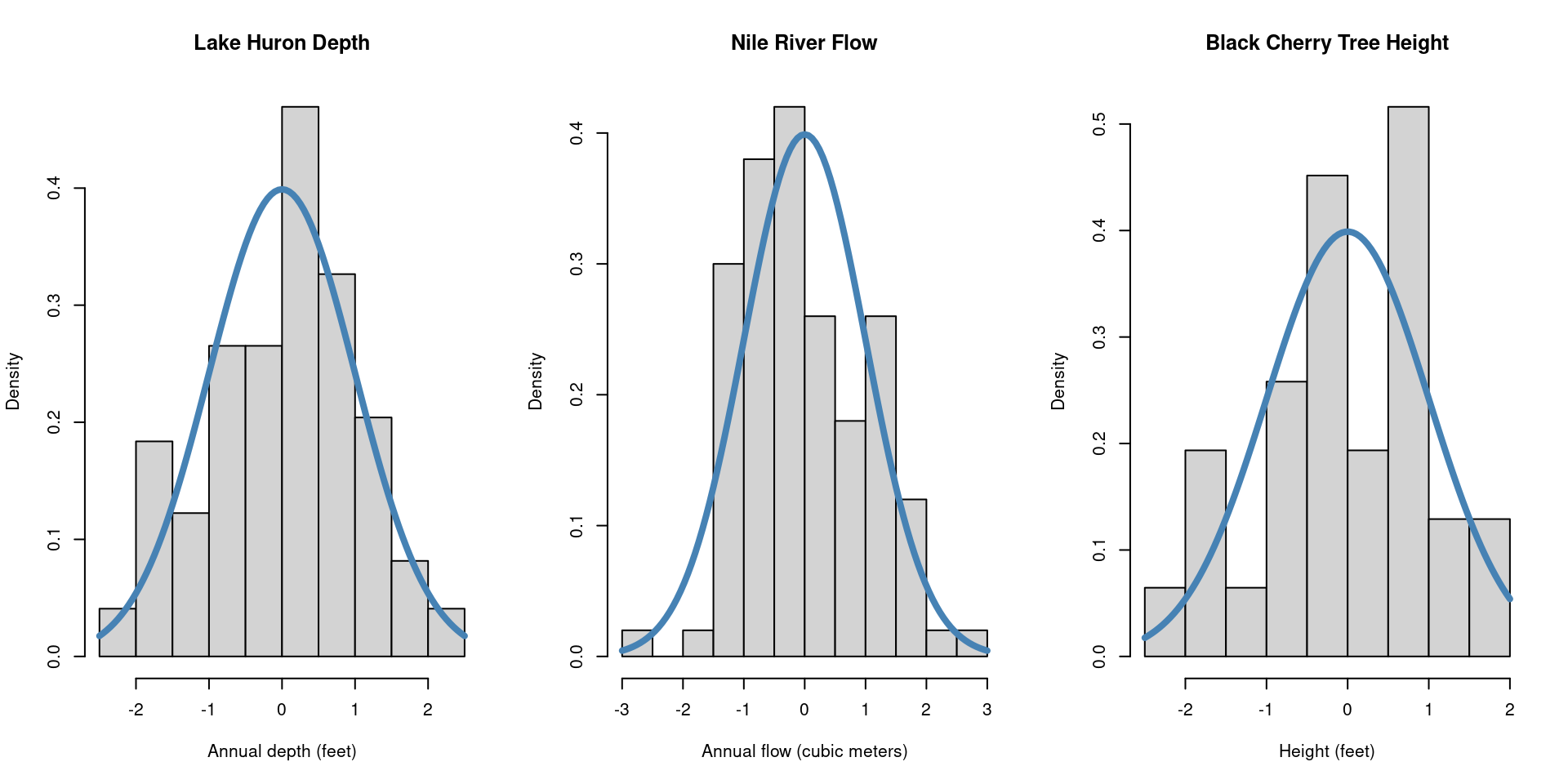

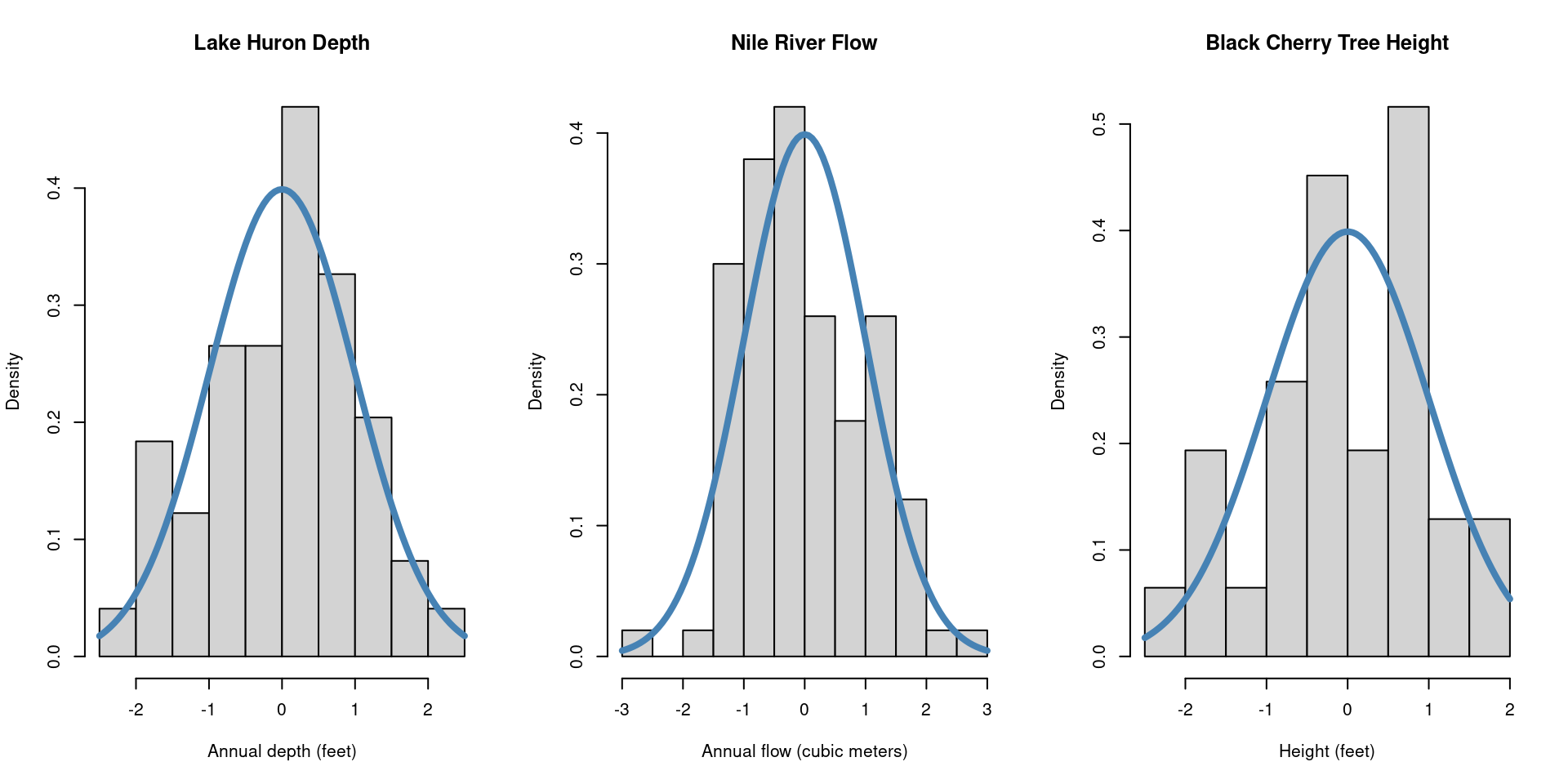

Let’s begin by considering three histograms, each describing a set of continuous

data collected from various sources. First, we have the annual depth of Lake Huron

from 1875-1972 measured in feet. Next, the annual flow of the river Nile from 1871-1970

measured in cubic meters, and lastly, the recorded height, in feet, of 31 black cherry

trees. What do all of these histograms seem to have in common?

What we see here are examples of a normal distribution (also known as a bell curve),

one of the most ubiquitous distributions in all of statistics. The normal distribution

is characterized by the “bell shape” that is symmetric about it’s center.

Like the binomial, the normal distribution is characterized by two parameters,

\(\mu\) and \(\sigma^2\), representing the mean and the variance, respectively. The

mean value, \(\mu\), indicates the location of the peak on the x-axis, whereas the

variance, \(\sigma^2\), indicates the amount of dispersion about the mean. A random

variable \(X\) that follows a normal distribution can be expressed \(X \sim N(\mu, \sigma^2)\),

or, “The random variable \(X\) follows a normal distribution with mean \(\mu\) and

variance \(\sigma^2\).” The formula for the normal distribution is given as

\[

\begin{align*}

f(x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi \sigma^2}} \ e^{- \frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}}.

\end{align*}

\]

Consider the two normal distributions below, with different values for \(\mu\) and

\(\sigma^2\). Although they are centered at different locations and have different

amounts of dispersion around the mean, they are both bell-shaped curves characteristic

of the normal distribution:

Given that the normal distribution appears so frequently in statistics, it is common

practice to standardize a normal distribution so that it has a mean value of \(\mu = 0\)

and variance \(\sigma^2 = 1\) (note also that the standard deviation is

\(\sigma = \sqrt{\sigma^2} = \sqrt{1} = 1\)). A normal random variable that has been

standardized is called a standard normal distribution and is often written

\(Z \sim N(0,1)\). We can consider again the histograms above, once they’ve been

standardized:

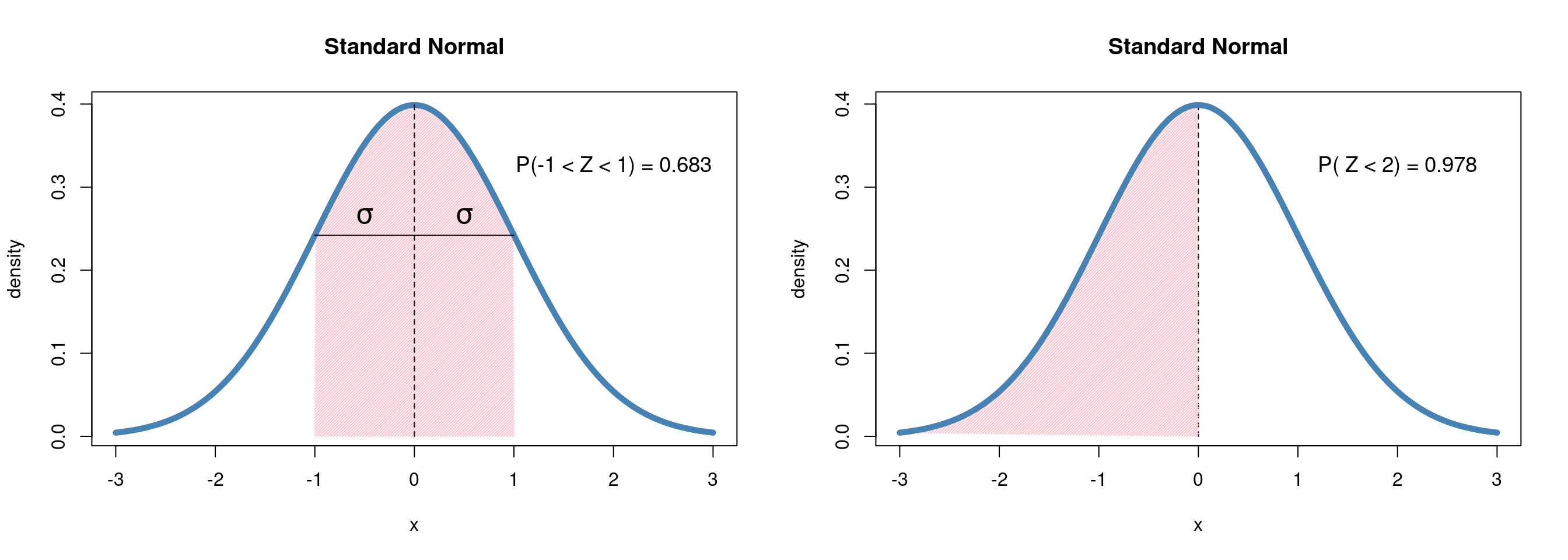

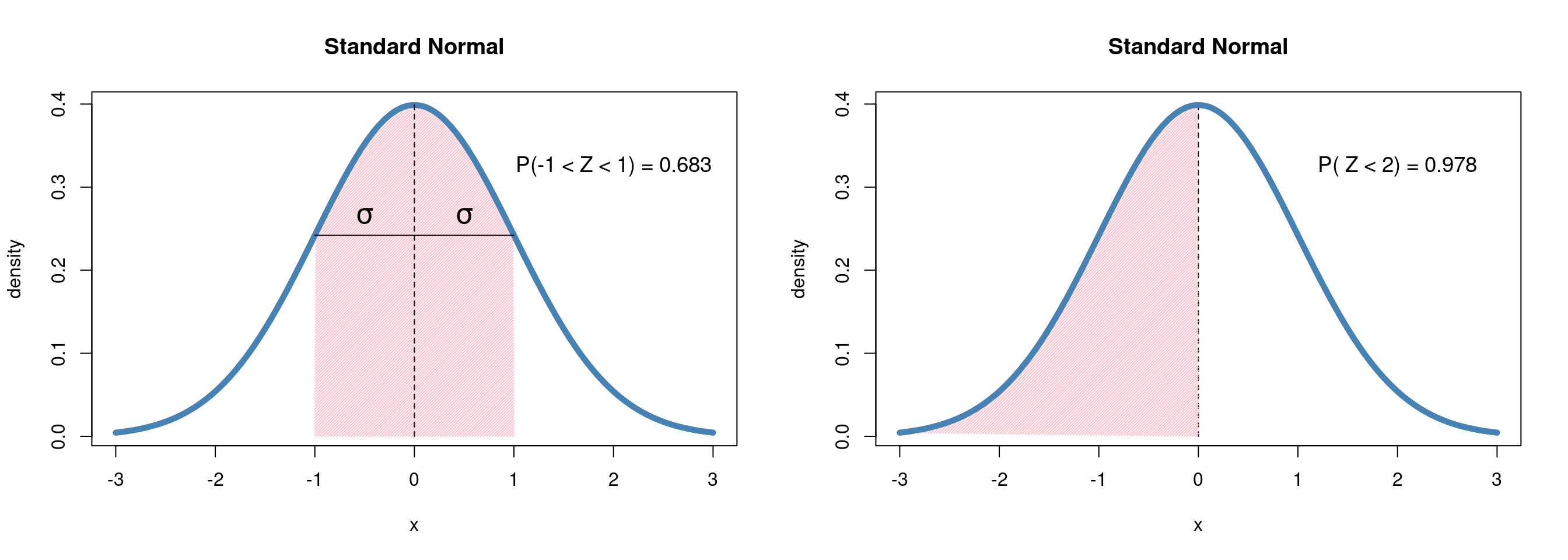

Unlike the binomial distribution, in which there are \(n\) possible values that our

random variable can take, the normal distribution represents a random variable that

is continuous over a range of values, making the normal distribution a member

of the family of continuous distributions. Instead of asking the probability

of a specific value, say, \(Z = 0\), probabilities are given as the area under the

curve for a certain interval. We might ask, “What is the probability that \(Z\) is

one standard deviation (\(\sigma\)) away from \(0\)?” or perhaps, “What is the probability

that \(Z < 0 ?\)”

We will return to the normal distribution in the following chapters, demonstrating

both how it arises naturally in the study of statistics and the powerful toolkit

it provides in the field of statistical inference.

The applet below is designed to help you get familiar with the parameters of the

normal distribution, and how they impact the probability distribution.

You can change the values of the mean \(\mu\), and

the standard deviation \(\sigma\), and the app will display the associated distribution

in a probability histogram.

Use the applet to answer the following questions:

Start by setting \(\mu = 0\) and \(\sigma = 1\). How would you describe the shape of the distribution? Is it symmetric? How concentrated are the range of values around zero?

Now set \(\sigma = 2\). What has changed? Reset the value back to \(\sigma = 1\) and press the “Play” button. How does the normal distribution change with \(\sigma\)?

Repeat exercise 2, this time setting \(\sigma = 1\) and allowing \(\mu\) to change over a range of values. How does the distribution change? How does it change compared with what we saw in exercise 2?

Play around with different values of \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\). What impact does changing \(\mu\) have on the concentration of values? How does changing \(\sigma\) impact where the distribution is centered? How would you describe the relationship between \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\)?

Compare your answers from this exercise with those from the binomial distribution. How do these distributions differ in their relationship to their parameters?

The applet below is designed to familiarize you with data generated from the

normal distribution. You can change the values of the mean \(\mu\), and

the standard deviation \(\sigma\) to specify the parameters of the population

distribution. Then, you can take a random sample from the distribution.

Use the applet to answer the following questions:

Start again by setting \(\mu = 0\) and \(\sigma = 1\), and simulate data several times with a sample size of 10. How does the observed data compare to the probability distribution? Does it have the same shape? What changes when we set our sample size to 50?

Compared with the binomial distribution, how well does data generated from a normal distribution tend to match the probability distribution? Given only the observed data, how close do you think your estimate would be of the underlying distribution?

Normal Distribution: A continuous bell-shaped distribution with

two parameters that are the mean value, \(\mu\), with a variance \(\sigma^2\)

Standard Normal Distribution: A special case of the normal distribution,

\(Z \sim N(0, 1)\)

Continuous Distribution: Any probability distribution that depicts the

occurrence of a random variable that can take an infinite set of possible values

within a given (potentially infinite) interval