Study design: The process of obtaining the best sample to answer the research questions

Scientific/Research Bias: Any process or technique whereby the actual outcome is systematically different from the true value it is intended to estimate

“Randomization is too important to be left to chance.”

— J. D. Petruccelli

There are many avenues by which data may land on the desk of a statistician. Many times, data is simply observational, that is, the data is collected by researchers without any control over independent variables. Such was the case with the La Guardia air quality data explored in Chapter 2, where in addition to temperature and ozone data, information was also collected for month, date, windspeed, and solar radiation. While this kind of study is useful for exploring the relationship between processes, it is often limited in its ability to make causal statements and inference.

More useful to researchers, and especially in biomedical studies, are those in which clinicians take a more proactive approach, manipulating independent variables in an attempt to determine a more direct relationship with an outcome, or the dependent variable. This is particularly important in studies that seek to determine the efficacy of a new drug or treatment. While there are a number of different designs that are used by medical researchers for a variety of purposes, we limit our discussion in this chapter to a broad class of studies known as clinical trials. More specifically, we will discuss a class of studies known as randomized controlled clinical trials, which are considered the gold-standard in medical research.

We will begin by addressing issues with variability and bias, followed by an outline of the procedures that typically go into a clinical trial. Finally, we will explore a list of specific biases that statisticians and researchers attempt to mitigate through effective study design.

In Chapter 1, we defined statistics by its ability to quantify uncertainty regarding the potential outcome of a random process. In order to do this most effectively and make accurate inference, researchers and statisticians do their best to remove potential sources of variability. Variability can manifest in a number of ways, ranging from the standard biological variability associated with a given population (genetic variation), as well as imprecision associated with measurement (measuring blood pressure, weight, etc.,). While these sources of variation do impact the ability to make precise inference, the effects associated with this kind of variability often “even out” in the end. In other words, though it may make inference less certain, it does not make it incorrect.

Similar to variability is the concept of bias. Whereas variability is used to describe the effects of random variation and imprecision, bias refers to a characteristics of a process or technique in which the measured outcome is systematically different from the true value it is meant to represent. For example, a researcher may be interested in taking the weight of patients at different times during the day. Due to fluctuations in metabolism, an individual patient may have a slightly different weight at different times of the day, resulting in variability. However, if the scale that is used is miscalibrated and always reports a weight that is ten pounds less than the true value, this would be bias. Unfortunately, there are very few tools at a statisticians disposal to address bias, and there is frequently no way to test if it is present or not. However, a well designed study can reduce this risk and put researchers and statisticians in the best possible place to perform successful science.

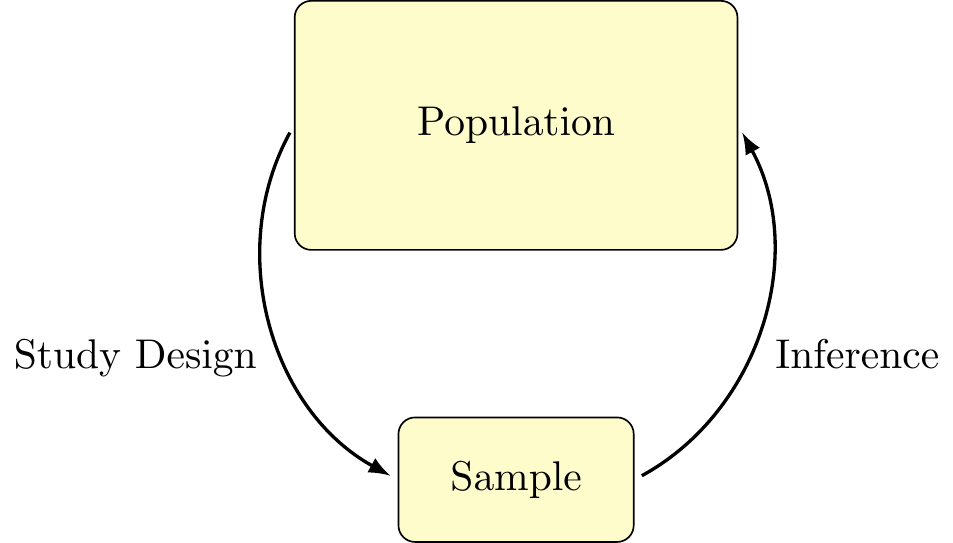

As a critical piece of the statistical framework, study design is the process of organizing, conducting, and analyzing a scientific experiment with the intention of resolving a hypothesis or achieving research goals. There are many types of study designs with various strengths and limitations, the entirety of which could not possibly be covered here. Instead, we will focus on some of the main considerations when designing a study, as well as the statistical implications associated with common ways in which study design can go wrong.

Figure 3.1: Statistical Framework

In an ideal world, the study design process might look a little bit like this:

Of course, real life situations are rarely ideal.

Bias can occur at various points during a research study and materialize in many forms. The ability to identify bias is a crucial skill for researchers to have when evaluating the merit of other studies in the literature or designing studies of their own. In this chapter, we focus on defining several common types of bias common in medical research, how each type can impact study results, and how they can be avoided. This is not meant to be an exhaustive list – if you are interested in learning about other types of bias, check out the Catalogue of Biases. We will categorize different types of bias broadly by when they occur: pre-trial, during trial, and post-trial, although all types of bias should be considered when planning a study.

Definition 3.1

Study design: The process of obtaining the best sample to answer the research questions

Scientific/Research Bias: Any process or technique whereby the actual outcome is systematically different from the true value it is intended to estimate

There are several phases involved in a formal clinical trial, with early stages focused on determining safety and evidence for potential efficacy of a treatment. Often, these trials are small, usually with numbers between 10 and 100 patients. Once enough evidence has been collected to demonstrate the safety and possible efficacy of an intervention, larger Stage 3 clinical trials are conducted, often with hundreds or even thousands of patients, and usually at multiple clinics or sites. Yet, in all cases, the general framework is the same. This helps ensure consistency across studies and sites and prevents researchers from introducing sources of bias that may unintentionally influence results. What follows are brief principles that are used to guide each step of the study process.

Before any study on human subjects begin, researchers are tasked with writing and proposing a study protocol that outlines who will be studied, what metrics will be collected, how the data will be analyzed, and a set of procedures to actively monitor the safety of the participants, as well as address how specific problems will be handled, if they arise. It is critical that these protocols are written and adhered to before a study begins; decisions that are made once the study has begun may be influenced by data that has already been seen. Further, specifying the main analysis in advance ensures that the hypothesis in question is being adequately answered. Without this safeguard in place, investigators may let the data observed direct the methods of analysis. This is known as data snooping, which can drastically impact the validity of the results.

Once the study protocol has been written, it is then submitted to an ethics/review board to ensure that subjects are treated fairly and humanely, and that all participants are able to give informed consent. This also helps evaluate the potential risks faced by subjects against any potential benefits from the trial. In the United States, this process is governed by an Institutional Review Board, or IRB. Further approval may be needed in cases involving the use of drugs or radioactive materials.

Before a study can begin, subjects must be enrolled and consent to performing in a study. Typically, eligible participants are selected for a study based on a set of eligibility criterion to ensure that subjects come from a population of interest. For example, in a study designed to test the efficacy of a new medication for lowering cholesterol, clinicians may only select subjects who have a demonstrated risk for heart disease. Similarly, it is often important to have a set of criteria that can exclude certain subjects, such as those with confounding issues that may make it difficult to limit the amount of variability in a study.

Of importance here is the fact that the results of study are only valid for populations from which the subjects in the study were drawn. If participants in a study are limited to a certain demographic, such as age or sex, then the findings may not hold for a more general population. This may result in a form of extrapolation bias, defined below, and is often a concern when extending treatment to minors, who are often not included in clinical trials.

In order to correctly estimate the efficacy of a treatment, it is vital to have a control group with which to evaluate it. In some cases, the control group may receive an existing method of treatment; in others, it may be a placebo, or inactive form of a drug or intervention. By collecting a study sample prior to assigning subjects to either a treatment or control group, researchers can minimize the risk that groups we are comparing differ in significant ways. To further minimize this risk, it is also necessary that a subject’s assignment to one group or another be conducted through a process known as randomization. If, for example, a study was to assign all participants at one clinic to the treatment group, and all participants from another clinic to the placebo group, there may be underlying differences between these groups that impact the results of the study.

For many clinical trials, researchers may choose to create sub-groups before initiating randomization to help control for any potential confounding effects. This process helps ensure that both treatment and control groups are similar in composition, for example, balancing the number of men and women or subjects within particular age groups. This is known as stratified randomization.

The efficiacy of many treatments can be influenced by perceptual or psychological factors of either the patient or clinician, especially in the evaluation of subjective measures such as pain or nausea. Further, the knowledge of which treatment a subject has been assigned may unintentionally bias the way a physician treats them, further complicating the study. To mitigate this, clinical trials often engage in blinding, in which either the subject, the clinician, or both, are unaware of the treatment assigned until the completion of the study. The case in which both the subject and the researcher are blinded is known as a double blind and has become standard practice for clinical trials.

Not infrequently, external circumstances or lack of compliance can alter the treatment that a subject in a clinical trial actually receives. As such, it is important that the study protocol outlines in advance exactly how such cases should be handled. Common practices utilizes what is known as intent-to-treat (ITT), whereby a subject is analyzed as being a member of the group to which they were assigned at randomization, regardless of the treatment that is actually received.

Pre-trial biases describe a collection of biases that can be introduced into a study before it even begins. Generally, these are associated with ensuring that our sample is representative of the population in question and that the study is designed in such a way that meaningful comparisons can be made.

The first major consideration when planning a study is who you will ask to participate. When selecting your sample, you must ensure the sample is representative of the population of interest. Otherwise, your study may be prone to selection bias, where the study participants differ systematically from the population of interest. For example, in the first phase of a vaccine trial, the vaccine is often given to young, healthy volunteers to assess its safety profile. However, the vaccine is intended for use for both young and older people, as well as those that may have underlying medical conditions. If the safety of the vaccine was only determined based on the initial studies in healthy participants, it would look safer than it really is. This is why these initial studies are primarily used to stop development of a vaccine that is unsafe. Vaccines that are found to be safe in healthy people proceed to further testing in the general population to accurately determine the safety profile. Selection bias can be avoided by careful consideration of the make up of the population and a sampling method that accounts for various sub-populations that may differ in respect to the study outcome.

We remarked earlier that in an ideal world, all selected participants would be eager to participate in our study. However, this is not always the case. To make matters even more difficult, sometimes those that want to participate in our study differ in meaningful ways from those that do participate. This type of bias, known as non-response or participant bias, can occur in many studies, but is often a particular concern for studies that send out surveys or election polls. For example, consider the end-of-semester teaching evaluations that provide students an opportunity to review their instructor anonymously. When students are not required to fill out these evaluations, it is likely that only students with strong opinions about their instructor will take the time to respond. This may cause the final evaluations to be a mix of very negative ratings and very positive ratings, whereas the instructor’s actual performance maybe be somewhere in the middle. Participant bias can be avoided when designing a study by reducing the survey length and offering incentives for participation.

To determine if a new treatment is effective, it must be compared to something else. This is addressed by splitting the sample into two groups: the treatment group and the control group. Subjects in the treatment group are given an active treatment, whereas subjects in the control group are not treated and are used for comparison. Subjects must be assigned to receive the treatment or control at random to avoid selection bias. In addition, there is the potential for bias to arise if the subjects know whether or not they’re being treated. This is known as confirmation bias, where the knowledge of treatment allocation can make study participants perceive the treatment benefit differently. To avoid this and ensure that any differences in the outcome are due to the treatment, researchers use a placebo, or inactive treatment (e.g. a sugar pill or saline infection).

Definition 3.2

Selection Bias: A type of bias in which subgroups of the population were more likely to be included than others.

Non-response/participant Bias: A type of bias in which non-participants differ in a meaningful way from the participants

Treatment group: The part of the sample that receives the treatment

Control Group: The part of the sample that is not treated for comparison purposes

Confirmation Bias: Bias due to an individuals prior beliefs

Placebo Effect: A psychological phenomenon where an inactive treatment can produce a positive response

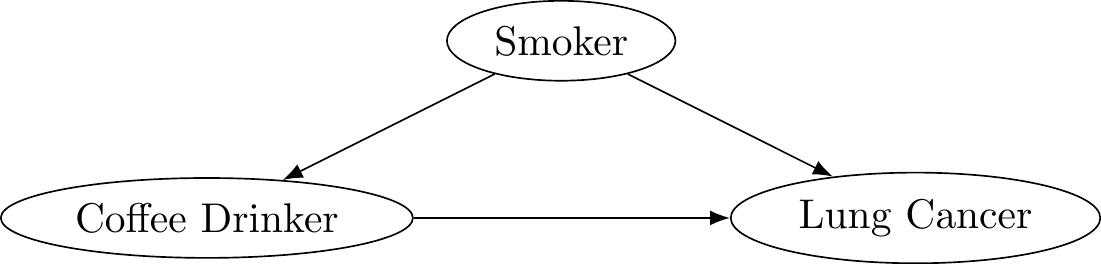

Many epidemiological studies have shown that coffee drinkers have an increased risk of lung cancer. However, upon further investigation, researchers also noticed that smokers are more likely to drink coffee. There is a known association between smoking and lung cancer, with people who smoke cigarettes being 15 to 30 times more likely to develop lung cancer than people who do not. Thus the association that was detected between coffee and lung cancer was not due to the coffee, and instead was impacted by smoking status.

Figure 3.2: Coffee causes cancer?

Once researchers controlled for smoking status, they no longer found a change in lung cancer risk due to drinking coffee. Smoking status is said to be a confounder, also known as a lurking variable. A confounder is a third variable related to both exposure and outcome. Because of this relationship, confounders distort the observed relationship between exposure and outcome.

Confounding can be avoided when designing the study by ensuring the treatment and control groups have similar distributions of each confounding variable. In the coffee and cancer example, this would be analogous to ensuring there were similar proportions of smokers in the coffee drinking and non-coffee drinking groups. If it is not possible to control for a confounder when designing the study, there may be other analytical methods that can be used.

Researchers often have expectations about how effective their treatment is (otherwise they probably wouldn’t be studying it). If the researcher is also responsible for recording subjective assessments of the study participants, there is the potential for their beliefs about the treatment to influence either they perceive a subject’s progress during follow-up.

Definition 3.3

Confounding: A third variable related to both exposure and outcome

Observer Bias: Bias arising when observers record subjective data

“To consult the statistician after an experiment is finished is often merely to ask him to conduct a post mortem examination. He can perhaps say what the experiment died of.”

— R. A. Fisher

Once a study has been completed, there is often very little that can be done to correct potential biases made during or before the study began. That being said, researchers still have a responsibility to present their findings in ways that can promote future research.

Despite individuals being willing to participate in a research study, this does not always mean they will comply perfectly with their assigned treatment. Consider an exercise study designed to help people lose weight. Individuals that are heavier and out of shape may tend to skip some of the workouts or drop out of the study at a higher rate than individuals that are in better shape prior to starting the study. Since compliance is directly tied to the outcome of interest (weight loss), bias may occur causing the exercise plan to look less effective than it truly is. Bias due to compliant participants differing from non-compliant participants is called compliance bias. Consider a 1980 study of the drug clofibrate, which is designed to reduce blood cholesterol levels to prevent coronary heart disease. Participants were randomly assigned to take up to three capsules of either clofibrate or placebo three times per day. At follow-up visits, the remaining number of capsules were counted to estimate how many each participant actually took each day. When comparing those that adhered (took at least 80% of their required capsules) to those that did not the study results were:

| # of Clofibrate Patients | Deaths | |

|---|---|---|

| Adherers | 708 | 15% |

| Non-adherers | 357 | 25% |

| Total | 1,103 | 20% |

When comparing adherers and non-adherers in the clofibrate group, we see that non-adherers were much more likely to die. This seems to provide strong evidence that clofibrate is effective, however we have ignored the results of the patients in the placebo group.

| # of Clofibrate Patients | Deaths | # of Placebo Patients | Deaths | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adherers | 708 | 15% | 1,813 | 15% |

| Non-adherers | 357 | 25% | 882 | 28% |

| Total | 1,103 | 20% | 2,789 | 21% |

When comparing patients in the clofibrate group to those that were on the placebo, we see the same trend of reduced mortality in adherers. Additionally, the death rate for adherers taking clofibrate is exactly the same as that for patients taking the placebo. This would indicate that clofibrate is not the reason for reduced mortality; instead, it is driven by characteristics of those that adhere to their medication. One possibility is that adherers are more concerned with their health in general, and are thus more likely to take better care of themselves. Compliance bias can be avoided by comparing subjects only by the groups to which they were randomized, despite their adherence to the treatment. This is also called intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis.

The previous two examples demonstrated ways in which we might incorrectly move from a target population to a non-representative sample. This final case describes movement in the opposite direction: from a specified sample to a more general population. Nonetheless, the cause of the bias is the same.

The motivation here can be most readily illustrated by considering the issue of pharmaceutical trails and the use of children. For practical, ethical, and economic reasons, clinical trials usually only involve adults – indeed, only about 25% of drugs are subjected to pediatric studies. Physicians, however, are allowed to use any FDA-approved drug in any way that they think is beneficial and are not required to inform parents if the therapy has not been tested on children.

Definition 3.4

Compliance Bias: Bias arising when those complying to study protocol differ from those that do not comply

Intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis: A method of analysis which includes all participants as they were randomized despite adherence